Artists

-

PHILIPPE ANTHONIOZ

-

ALEXANDRA ATHANASSIADES

-

BEATRICE CASADESUS

-

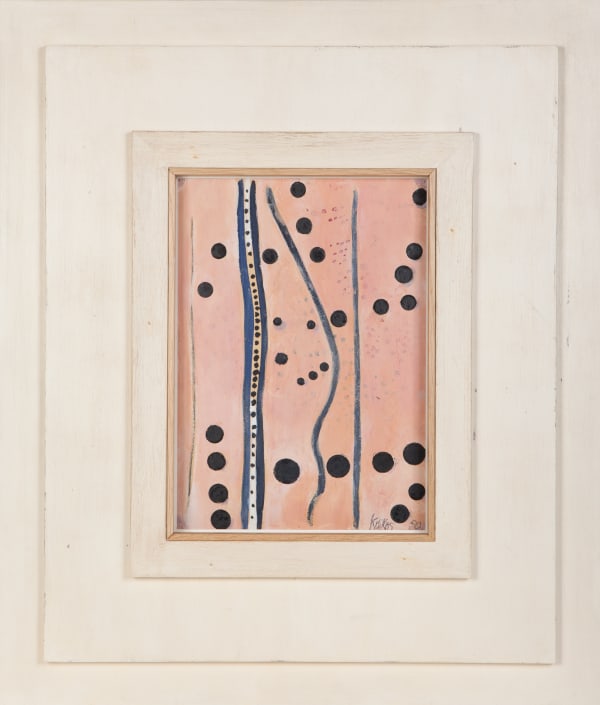

KATSUMATA CHIEKO

-

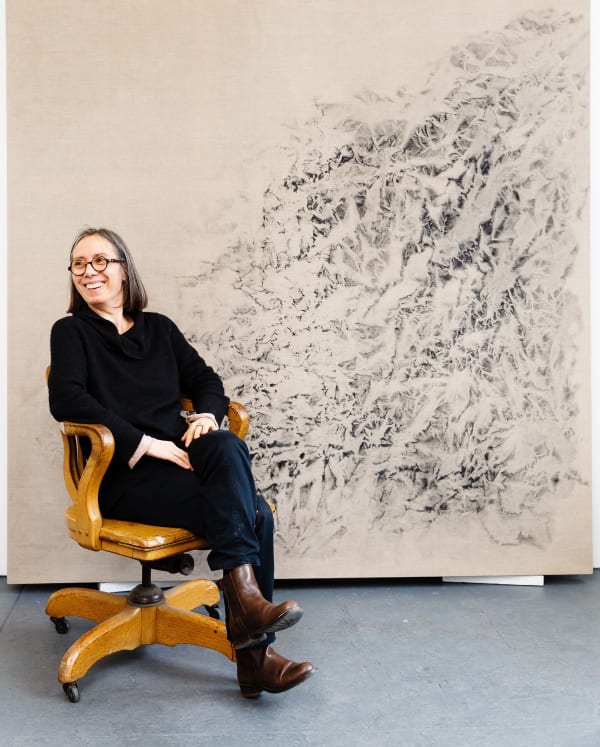

VICKY COLOMBET

-

ROBERT COURTRIGHT

-

MONIQUE FRYDMAN

-

GARNIER ET LINKER

-

CHRISTIAN JACCARD

-

Tegene Kunbi

-

Jean-François Lacalmontie

-

TED LARSEN

-

GUY LECLERCQ

-

BENOIT LEMERCIER

-

PATRICK NAGGAR

-

JEAN-PIERRE PINCEMIN

-

BRUNO ROMEDA

-

ERIC SCHMITT

-

CHRISTIAN SORG

-

Marek Szczesny

-

Lucas Talbotier

-

Hitomi Uchikura

-

MAX WECHSLER

-

Vladimir Zbynovsky

Projects with